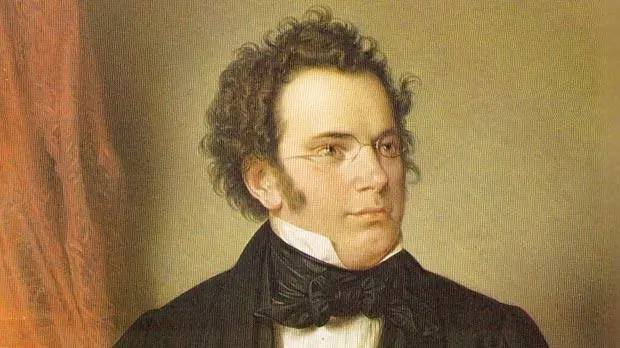

Why Schubert wrote 4-hand piano music when he was dying

Album Of The WeekFrom the Lebrecht Album of the Week:

Franz Schubert, in the final year of his short life, feared he was dying and hoped he was not. Some doctors thought his symptoms were neurotic (this was Vienna, after all), others suspected a consequence of his mercury treatment for incurable syphilis. Schubert, 31 years old, kept on composing between bouts of vomiting, headaches and excruciating pain in his joint. Among the awesome outpouring of 1828 are the great C major symphony, the unsurpassed string quintet, three last piano sonatas and the so-called ‘Swansong’ song cycle.

Apparently trivial by comparison are four works for piano duo, intended for home use….

Read on here.

And in The Critic.

En francais ici.

No. The Great C major symphony dates from 1825 – 1826, not 1828. The dating to 1828 was popularly accepted for decades but this was disproved by Professor Brian Newbould, in his book ‘Schubert and the Symphony’ (1992). This is a ‘must’ for anyone interested in Schubert’s symphonies and symphonic fragments. Newbould is arguably the world’s greatest living authority on this subject. This fascinating book is meticulously researched and eminently readable.

In 1824, Schubert had written a letter to his friend Kupelweiser saying that he intended to write ‘a grand symphony’. There was no sign of this mysterious work though, which was referred to as the ‘Gastein’ symphony. Various theories were mooted, including the possibility that the Grand Duo sonata was a piano reduction of this work; Joachim even made a very fine orchestral arrangement.

But by meticulous research, including examination of the manuscript paper on which the symphony was written, Newbould proved beyond doubt that the Great C major symphony was indeed the elusive Gastein symphony referred to in that letter of 1824.

Scholars no longer think that the Great C Major Symphony was composed in the last year of Schubert’s life. It is now believed to have been composed around 1825/26.

Indeed and if i remember well ,some 50 years ago,this 9th symphony was then with a lower number.I can’t remember which one.7?

So Richter and Britten played the D Minor 4-Hands Fantasie because they were “two midlife gay men who each found something about themselves in this delicate and deceptive domestic fantasy”?

And that makes Radu Lupu and Murray Perahia giggling and winking as they cosily noodge shoulders through the D Minor Fantasie, what, a couple of lumberjacks?

It’s in F minor (both times).

Nice one, ParallelFifths – though I think that you meant the F minor Fantasie – not D minor (and not Fantasia, as NL would have it). Maybe pedantic points thus far, but…

This article about Schubert’s four piano duet works of 1828 is headed ‘Almost too poignant to bear’ and NL then goes on to dismiss these four works as ‘relatively trivial’ while, in the same breath, he admires the ‘formal perfection’ of the Fantasie. Forgive me, but I am confused.

Far from this Fantasie being a ‘trivial’ (as NL would have it), cosy, domestic piece of Biedermeyer kitsch, this is a sublime masterpiece dating from Schubert’s last year. Lebenssturme, another work on the CD, is also a powerful and passionate work. The urbane A major Rondo is closest to being a sociable stroll in the sunshine – lovely though it is. Only the fugue in E minor is of little musical interest – just an academic exercise in counterpoint.

As for the implication that throughout 1828, in his last year, Schubert ‘kept on composing between bouts of vomiting, headaches and excruciating pain in his joints’, this is not really the case. He has been diagnosed with syphilis about five years earlier but had so far experienced only the relatively mild symptoms of the disease. In his final year, having completed about 45 works, these dreadful symptoms appeared very late in 1828, just days before his death and may not have been attributable to syphilis. While his health had been undermined by the early stages of the disease and by the use of mercury treatment, he had moved into his brother’s new house but the plastering was not yet dry and the house was damp. He contracted typhus, and it was that which probably caused these dreadful symptoms and his death a few days later, on 19th November. But by that time, all the works of his final year had been completed and all he was working on when he died was copious sketches of a tenth symphony. This may have been a merciful release, given the effects of tertiary syphilis experienced by Schumann, Smetana and Hugo Wolf, for example.

Regarding Richter and Britten’s performance of the F minor Fantasie as ‘two midlife gay men who each found something about themselves’, failing any documentary evidence that either of the performers felt that way, this itself is a fantasy and not worthy of serious consideration, trivialising the work of these two great musicians.